Tired, but somewhat refreshed for the New Year; apologetic, for the unannounced and mostly unplanned December quasi-hiatus; busy, due to a new contract at the day-job, or day-business rather, which may affect volume somewhat, but it should still certainly be better than said December quasi-hiatus.

I think that about sums it up.

Also, I see that thanks to two more Patreon pledges – thank you kindly, if you’re reading this! – we have now crossed the reward threshold at which there will be artwork.

Oh, god, I promised y’all artwork.

Welp.

I’ll get right on that, then.

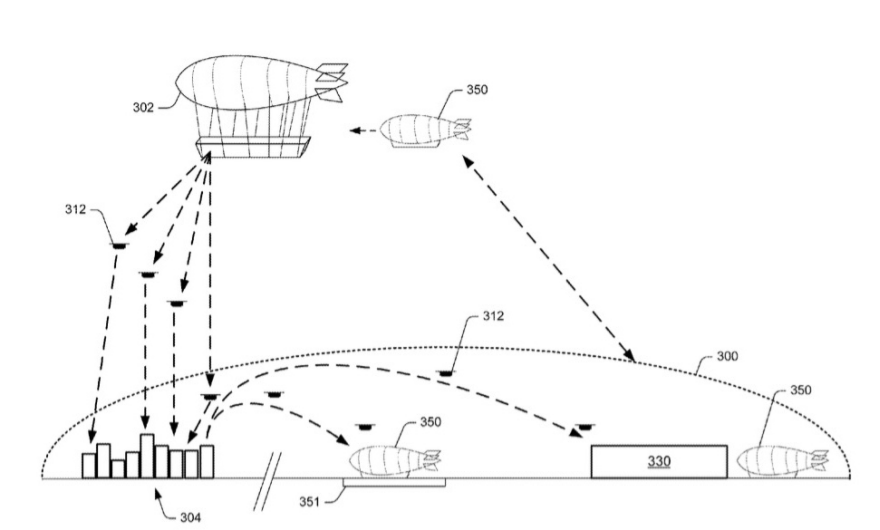

Also also, just as a side-note, this is Amazon’s recent patent filing on airborne warehouses with drone delivery:

…I hereby declare this to be exactly how, in canon, the All Good Things, ICC delivery service works on garden worlds, on the grounds that (a) the Imperials do love their airships, and (b), it’s freakin’ awesome.