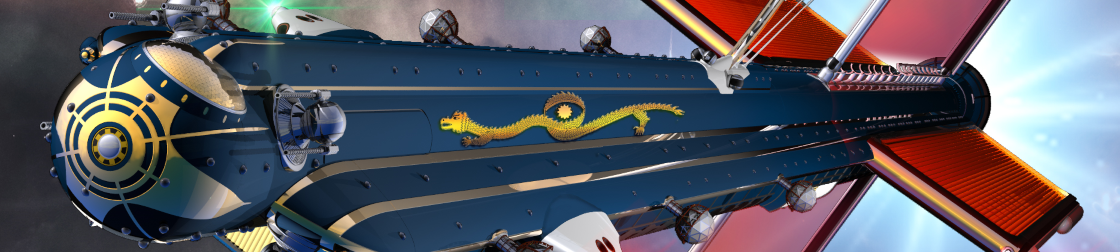

The Spaceflight Initiative Flight Center was built at the far western edge of the Bright Desert where the mountains come down to meet it, next to the hundreds of square miles set aside as the Orbital Launch Reservation. The Center itself perches on land cut out of the edge of the mountains, and back into the mountains; even when the Initiative was first proposed they knew that they’d be relying on nuclear pulse drives, and the cold wind that’s always blowing off the slopes keeps the launch fallout at bay.

When you arrive at the Center, down from the mountains or up from the trains, you’re at the west end of Starflight Drive. There’re roads going off to either side and back into the underways, and a couple of big cuttings going down into the desert, but the Drive itself is a straight shot from the entrance right to the far side of the Center, where there’s a little stubby white box of a building built right into the cliff edge. There’s a much bigger modern building there too, now, sitting almost right on top of it – that’s the new Operations Control, because they still run experimental flights out of the Center today. The old one’s a museum now, showing off simulations of the old flights to visitors, but that little white bunker was where everything happened in the early days.

But before you reach Opscon, you come to a section of the Drive lined with weeping blackwood trees and golden statues, each one with its own plaque, inset letters giving mission and crew names. Swiftrunner. Sunscraper Four. Redblossom Twelve. Oculus Forty. Copperfall One. Oculus Three. And just before you reach the bunker entrance, the last statue – a golden astronaut dressed in one of the old soft-shell crew suits, upraised fist clenching the lumpy shape of a drive pellet and, at her feet, a fragment of hull-metal blackened and seared with plasma scoring.

Phoenix Five

Meris Claves-ith-Lelad

Elissa Corith-ith-Corith

Alvis Peressin-ith-Perise

That one was mine.

* * *

I was public affairs at Opscon for Five, and it had been an excellent mission from that point of view so far. Everyone on the planet was behind the Initiative that year.

It was a cold spring day when Five was scheduled to return, and we were confident. We’d had five previous flights go up and return without anything but a few glitches in the secondary systems. The Phoenix stack worked. And the rest of the mission had gone perfectly. The new communications array checked out, twelve by twelve. The research labs were already cooing over the results of Alvis’s microgravity experiments, and clamoring to get their hands on them once they landed. And Elissa’s spacewalk had come together perfectly, first time. Fourteen minutes outside the vehicle; no pressure loss, no ballooning. Able to maneuver; indeed, able to maneuver elegantly.

And we had an experienced crew for the first time. This was Meris’s – Meris ith-Lelad’s – second flight; she’d been second pilot on Phoenix One the previous year. Were we less prepared for something to go wrong? I don’t think so; we all understood we were pushing hard into the unknown. But we were certainly expecting it – I was certainly expecting it – less than we had been.

She was in re-entry phase, balancing on her pusher plate, when it happened, having entered loss-of-signal at 76 miles up, and I’d finished giving the usual briefing to the press. All normal, nothing to worry about, even if being out of touch did raise the level of tension around here. I was halfway through recapping earlier parts of the mission briefing to keep them busy – we’d learned on Zero that it did nobody’s calm any good to have the press asking questions during the white-knuckle no-communications, no-telemetry part of the flight – when the discreet anomaly light lit up on my console, telling me to wrap it up and clear the room.

I don’t remember what I said then. I do recall that they left the press room a lot more quietly than I was expecting, but all I can remember is staring through the window at the radar display, where the blip showing Five in her descent had elongated to a streak. There was debris coming off the ship.

By the time I got down to the control room, we’d got partial telemetry back. Beran ith-Issarthyl – flight communications – was calling over and over. “Phoenix Five, Opscon, do you read? Phoenix Five, Opscon, confirm status,” but the board was lit up, crimson as death, with the status we did have. ACS BURN. Attitude thrusters firing, which wasn’t a part of any entry program. AXIS INSTABILITY. Which explained the thruster burn, at least, but — BUNKER LOW WARN. HYD2 PRESS LOW. C BUS UNDERVOLT. VIBRAT EX-PARAM.

The radio crackled and spat, then produced words. Meris’s voice, loud over a roaring that for one lunatic moment I thought might be static, but was the roaring of the ACS jets trying to nail Five in the right attitude for entry, keep her balanced, keep her alive…

“–scon, Five, do you read? Opscon, this is… nix Five… you read?”

“Yes, Five, we have you. This is Opscon. Report status, please. We show…”

“Anomalous readings and debris, yes.” Her voice stayed calm, professionalism overcoming strain, and I tried not to think about just how bad things must be in the ship that I could hear any strain in her voice. “Status is pessimal, Opscon. We had structural failure about four minutes into LOS. The port-dorsal pellet silo is gone, looks like it pivoted outside the plate shadow. I say again, the port-dorsal pellet silo is gone. By the system failure pattern, we’ve got penetrations all along the core structure. Sssht–abin integrity stable, for now. Over.”

“Five, Opscon. Acknowledge your status… ah, wait one, Five, we’re running models. Over.”

“Time’s running out, Opscon. Static moment’s shot all to dark with the silo gone. We’re running the ACS at hard burn to maintain attitude. ACS fuel remaining shows 15% and dropping. Estimate four minutes remaining. Over.”

Running feet. The rustle of engineers paging hurriedly through blueprints. A babble of voices, suggestion after suggestion, none viable. No way to use the gyros to stabilize. Not enough fuel pellets left to abort back to orbit even without the missing silo, and even if the core penetrations hadn’t wrecked the ship’s ability to stand up to thrust. No way to get more fuel to the ACS…

“Opscon, Five.” The signal cut through the chatter. “ACS fuel remaining now 7%. Stable flight time now one point five.” A pause before her voice returned, all strain now gone from it. “We’re, ah, all agreed up here. Are we go for STARBURST?”

Program STARBURST. A contingency that we never briefed the press about. The Phoenices were big ships compared to anything we’d put into space before, or that had burned up harmlessly on the way down. If Five went into tumble, she’d shred, and tear, and melt, and kill her crew, but she wouldn’t burn up… and shortly thereafter, most of her six thousand tonnes of flaming metal and plutonium fuel would come slamming back to earth in a few large pieces – and so we all knew that the one thing that couldn’t be permitted was for her to come down in those pieces. STARBURST existed to ensure that, in the simplest way that a nuclear pulse-drive ship could.

I looked across the room, all chatter stilled, at Beran. Tears were running down his face – my own face was wet, not that I’d noticed – but he kept his voice steady as he replied. “Five, Opscon concurs. You are go for STARBURST. Go well, my friends. You will be remembered.”

“Roger, Opscon. Programming for STARBURST now. Tell our families we love them. Tell Six… tell Six to have a drink for us when they get up here.” A burst of static. “It was a good fli-”

Nuclear fire blossomed in the desert sky. Phoenix Five had fallen.

Dedicated to the crews of Apollo 1, Soyuz 1, Soyuz 11, Challenger, Columbia, and all the other astronauts and cosmonauts who have died furthering the cause of human spaceflight. Per ardua, ad astra.