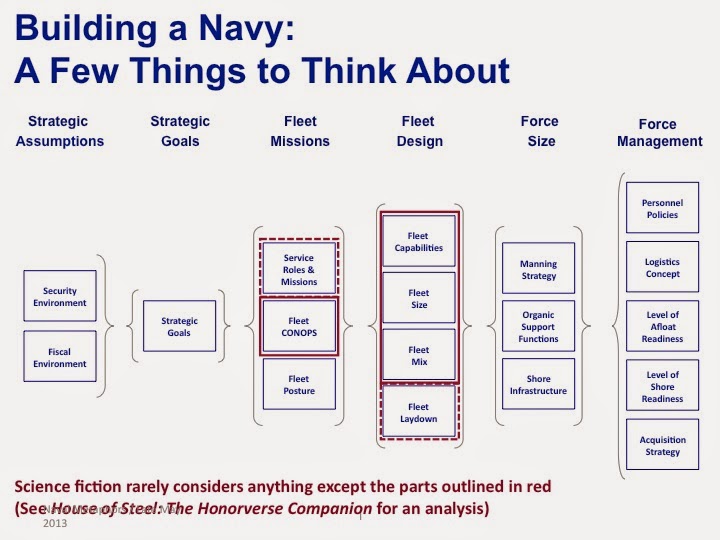

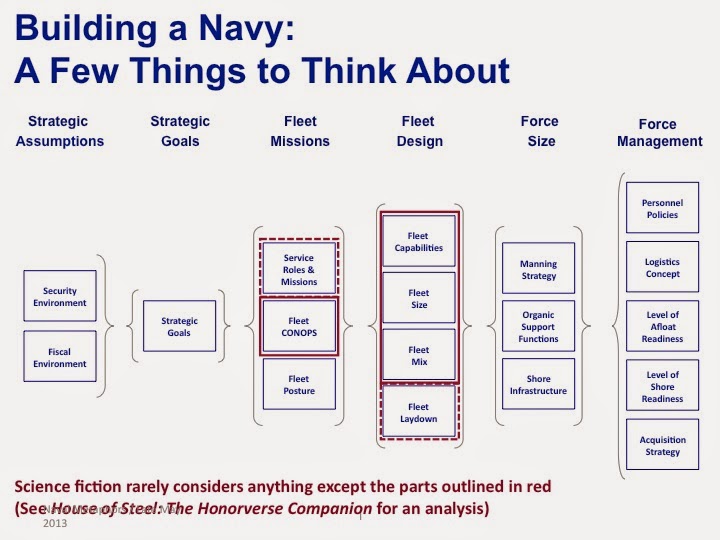

This is the third part of our six-part series on Building the Imperial Navy (first here; second here), in which we extend the strategic goals we made in the second part by defining the Navy’s role relative to the other parts of the Imperial Military Service, and define in general terms what the fleet does in support of its missions. In this step, there are three sub-steps:

This is the third part of our six-part series on Building the Imperial Navy (first here; second here), in which we extend the strategic goals we made in the second part by defining the Navy’s role relative to the other parts of the Imperial Military Service, and define in general terms what the fleet does in support of its missions. In this step, there are three sub-steps:

Service Roles & Missions

What services (the Navy included) exist, and which parts of the larger strategic puzzle are allocated to each service? Which types of mission does each service consider a core capability? How does the Navy support its own missions, and what services does it offer to the other services – and vice versa?

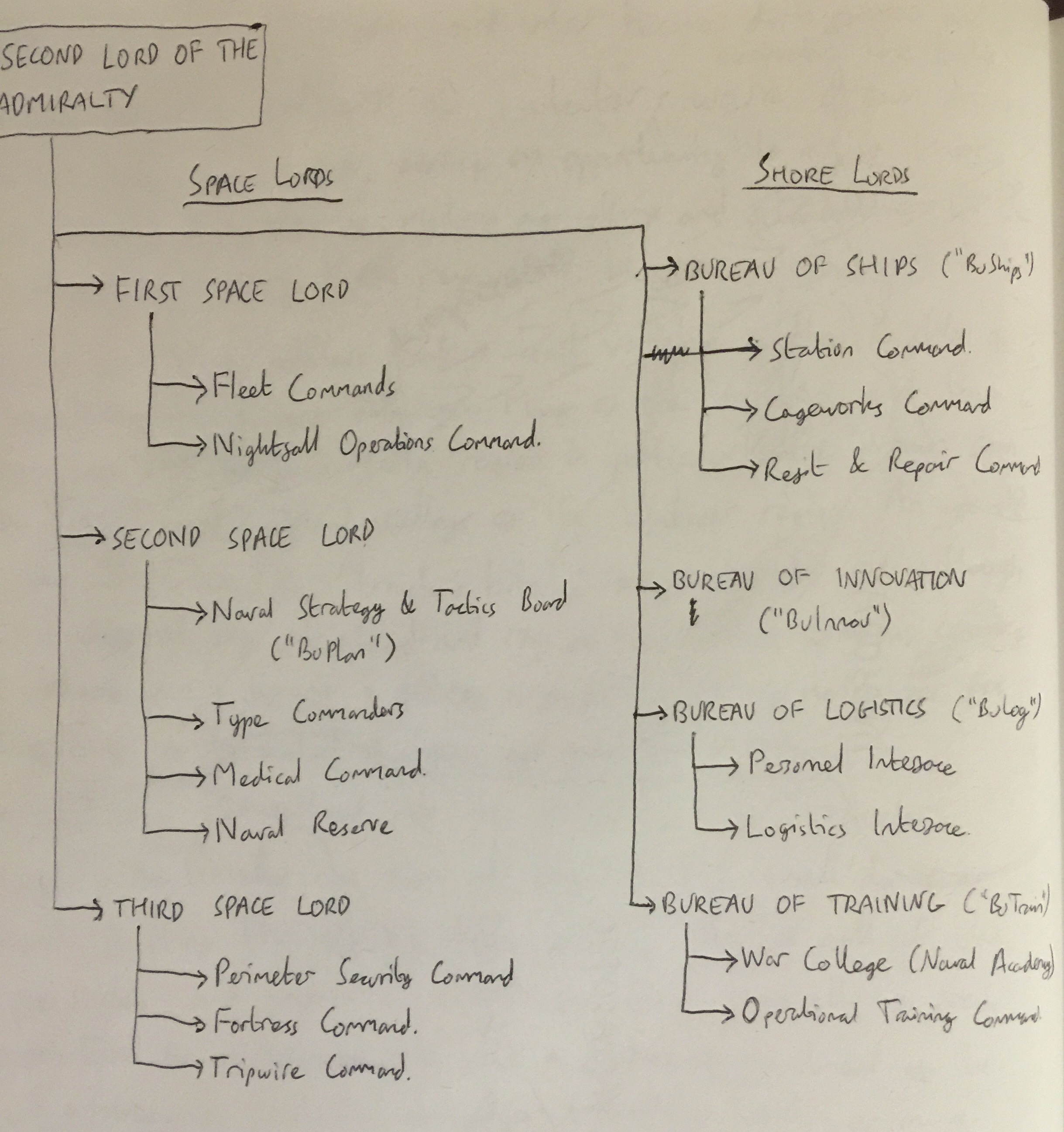

In the Imperial Military Service, the Imperial Navy is definitely the senior military service, as tends to be the case for any interstellar polity. While (in a relatively unusual case for a star nation) it does not directly control the other services – that being the responsibility of Core Command and the Theater Commands – IN admirals dominate these by the numbers, and strategy is heavily driven by fleet actions.

The IN is, after all, tasked to provide all combat and patrol functions anywhere in the Worlds (and, quite possibly, anywhere else in the galaxy), along with all necessary support functions for the Legions when operating outside the Empire or off-planet within it, and any support functions required by the other stratarchies likewise. With a remit like that…

Well. The First Lord of the Admiralty may be officially styled Protector of the Starways, Warden of the Charted Void, Warlord of the Empire, but it’s the Second Lord, the Admiral of the Fleet, who rejoices in the nickname “King Of All Known Space”.

To achieve all of this, the majority of the Imperial Navy is organized into a number of fleets: the Home Fleet, the Capital Fleet, and the “directional fleets” – the Field Fleets Coreward, Rimward, Spinward, Trailing, Acme, and Nadir. The first of these, the Home Fleet, is based at Prime Base, Palaxias, and is the garrison fleet for the Imperial Core and Fringe, keeping up patrols and strategic defenses along access routes; meanwhile, the Field Fleets operate outside the Empire, each in its assigned sextant, providing continuous patrols and security services from their associated fleet stations.

Capital Fleet, meanwhile, has a double name: on one hand, it is the defensive fleet for the Capital District, the throneworld, Conclave Drift, Corícal, Esilmúr, and Prime Base itself. On the other hand, it also possesses the highest proportion of capital ships in the Imperial Navy, because it forms its major strategic reserve in the event of war breaking out, and is also the fleet from which flotillas and task forces to handle situations that the lighter units of the Field Fleets cannot is formed from. As such, curiously enough, it’s probably also the fleet that sees the most full-contact military action.

There are also certain very specialized functions (command of certain fixed defenses, including tripwires and englobement grids; anti-RKV defenses; the RKV deterrent fleet; relativistic war operations; and so forth) using equally specialized starships that don’t fit neatly into the fleet structure, which are grouped together under specialized areas such as Nightfall Operations Command, Perimeter Security Command, Fortress Command, Tripwire Command, and so forth.

The Imperial Legions are the Empire’s “ground” combat organization, with the understanding that in this case “ground” includes in habitats, on asteroids, in microgravity temps, underwater, and basically anywhere else you can’t fit a starship, including starship-to-starship boarding actions.

They serve both as onboard “ship’s troops” – providing shipboard security, boarding and landing forces, and additional damage control personnel – and as an offensive combat arm with their own assault cruisers, drop pods, shuttles, and ships, and organic light and heavy armored cavalry, which is attached to Naval task forces as required.

The Navy, in turn, is responsible for the Legions’ transportation, escort, and orbital fire support.

As the possessor of the “misc”, various specialized forcelets that don’t fit anywhere else, the Stratarchy of Military Unification is called upon by the Navy and the Legions when they need one of those specialties somewhere, relies upon them for transport, etc., and otherwise has a similar but much less called-upon relationship to the Navy-Legions one.

It is perhaps notable that the Empire has no “Army”-equivalent service: i.e., no branch concentrating on mass warfare, long-term occupation, etc., the Legions being highly specialized in the raiding/commando/special operations/strike-hard-and-fast role. This is entirely deliberate, as the Empire has chosen a policy of deliberately eschewing those types of warfare in the current era[1] to the extent that they are not substitutable. This policy is intended to have a twofold effect:

First, reassurance of the Empire’s neighbors with regard to its own peaceful intentions; the Empire may have a large and potent military force, but any strategic planner with eyes should be able to tell instantly that it is extremely badly adapted for attempts at conquest, and would need considerable reengineering to become a suitable tool for setting out on imperial adventures.

But second, of course, those hostile polities or sub-polity factions whose strategic calculus might let them conclude that they can get away with fighting a long guerilla war against an occupation should think twice when it’s equally obvious to the trained eye that that isn’t one of the options on the Empire’s table, and that the most likely substitution from the force mix they do have is to blast them back into the Neolithic with orbital artillery.

(Occasional miscalculations on this point in the Conclave of Galactic Polities have led to accusations of “k-rod peacekeeping” and on one occasion the Cobalt Peace Wall Incident, but it’s unlikely to change any time soon.)

The IN coordinates its operations and provides transportation (when necessary) for the Stratarchies of Data Warfare, Indirection and Subtlety, and Warrior Philosophy, as well as certain other special services (like, say, preemptively burying hidden tangle channel endpoints where they might be useful). By and large, coordination is the main relationship: Indirection and Subtlety, for example, might consider it a failure if they’ve let things get to the point of there being a war at all, but as long as they’re doing assassinations and sabotage in wartime, it is best if it happens at the appropriate time, belike.

Their biggest relationship apart from the Legions is with the Stratarchy of Military Support and Logistics, which owns the oilers, the logistics bases, the transportation and supply contracts, the freighter fleet, medical and personnel services, etc., etc., and basically all the other logistical back-end needed to run the Military Service that the Navy would be doing for itself if the people who designed these systems didn’t much prefer that they concentrate on specifically naval things. They work closely together to get logistics done, and in wartime, ensure that the logistics functions are adequately escorted and otherwise protected.

The IN has very little at all to do with the Home Guard, it being a domestic security militia force only.

Fleet Concept of Operations

In general what does the fleet do? When and where will the fleet execute the missions defined in the last step? Will the fleet fight near home, along the border, or will it fight in enemy territory? Is it offensive in orientation, or defensive? What’s the standard operating procedure?

In orientation, by and large, the Home Fleet is defensive; the Field Fleets are mostly offensive (although less so to spinward and nadir, where they rub up against the borders with the Republic and the Consciousness, respectively); and the Capital Fleet, which can be called upon to reinforce either, splits the difference with a bias to the offensive side.

On the defensive, the rule of thumb is, as it has always been, “fight as far from whatever you’re trying to defend as possible”. Space battles are messy, and if at all possible, you don’t want to be fighting them with anything you care about preserving as the backstop. Home defense, therefore, involves a “hard crust” – although one backed up by a “firm center” – around the core Empire’s connection to the greater stargate plexus, but expands this by placing pickets, and of course the “field fleet” patrols, well in advance of these. The intent is that the defensive fleets should advance to meet any attacker and take them out, or at least greatly reduce them, before they ever reach Imperial territory.

And, of course, the best defense is a preemptive offense – when Admiralty Intelligence and Indirection and Subtlety can arrange that.

On the offense, the IN adheres to the military doctrine the Empire has always practiced, given various factors previously discussed, namely that only an idiot chooses a fair fight, and only a double-damned idiot fights anything resembling a frontal war of attrition. Misdirection, whittling flank attacks, deep strikes on crucial nexi, and eventual defeat in detail are the hallmarks of the IN’s strategy on the attack.

In terms of scale of operations, the IN plans for disaster: conventional readiness standards call for the IN and the rest of the Military Service to be able to fight three major brushfire wars simultaneously and/or one sub-eschatonic war (i.e. one step below ex-threat, like invasion from a massively larger polity such as the Republic or an unknown higher-tech polity), even while sustaining normal operations. The former, at least, is known to be possible. The latter… has not yet been tested in a completely stringent manner. But that’s what the Admiralty is planning for.

Fleet Posture

Is the fleet forward deployed (so that it can rapidly deploy to known threats) or based outside of the home system(s)? It is garrison-based, i.e., homeported in the home system(s)? Does it conduct frequent deployments or patrols or does it largely stay near home space and only go out for training? (Fleet posture is not where the starships are based, but instead how they are based and how forward-leaning it is.)

The nature of superluminal travel in many ways defines the nature of the strategic environment. Since travel between star systems is normally done using the stargates, a surface defined in terms of a list of stargate links can be treated, effectively, as a border or as an effective defensive line. While it is possible to bypass such a surface by subluminal (relativistic) travel, this is a sufficiently difficult and expensive process (and one requiring specialty hardware) as to make it a minor strategic consideration, for the most part.

That, at least, frees the IN from having to picket every system all the time.

That said, its posture is as forward-leaning as they can make it. Both the Home Fleet (within the Empire) and the Field Fleets are kept in constant motion, on patrol; the field fleets, in particular, travel on randomly-generated patrol routes from the Imperial Fringe out into the Periphery via various fleet stations and then return, throughout the entire volume of the Associated Worlds. (This requires a great many agreements with various other polities for passage of naval vessels, usually gained with the assistance of Ring Dynamics, ICC, who find this desirable with reference to the defense of their stargates.) Constant motion is the watchword: the IN doesn’t want its task forces to be pinned down or for it to be known where they are at any given moment, and this additionally helps make it very likely that anywhere there’s a sudden need for a task force, there will be starships available for relatively ready retasking. (I say relatively ready: the nature of stargates means that while you can cross from star to neighboring star instantly, you have to cross the star systems in between from stargate to stargate the slow way – and while brachistochrones at single-digit gravities are skiffily impressive by Earth-now standards, they still aren’t exactly express travel between, say, two points 120 degrees apart on the orbit of Neptune.)

The Field Fleets are, in short, about as forward-leaning as it’s possible to be.

The Capital Fleet spends more time in garrison, by its nature, but in addition to training operations, units and squadrons are routinely transferred back and forth to the Field Fleets or dispatched on special operations so that every IN unit maintains at least a minimum degree of seasoning. It’s the view of the Second Lord and BuTrain in particular that a Navy that doesn’t fight is likely to be bloody useless if it ever has to fight, so it’s best all around to keep everyone out there as much as practicable.

[1] In previous eras, such tasks were the responsibilities of the Legions: should they be needed again, the remit of the Legions is likely to be once again expanded.